In the fourth article of this nine-part series on ethics in the workplace, Luke Andreski investigates what it means to be an ethical colleague, beginning, in Part 1 of this discussion, from the striking viewpoint of Systems Theory and Complexity Analysis.

In previous articles in this series I’ve talked about the nature of ethics and outlined three basic moral aims which we can use in assessing the morality of our businesses and our own management practice. These are:

I’ve discussed what it means to be an ethical business, and how to be an ethical manager within any business.

Now I’d like to get personal.

I’d like to talk about you and me. I’d like to talk about us.

And I’d like to talk about how ethical standards and behaviour are of critical importance to all of us, regardless of our position or the type of business in which we work.

The workplace is a wonderfully complex entity. It is in fact what any professor of Complexity Theory would call a Complex Adaptive System.

This complexity introduces into our workplaces two crucial features:

(1) Fragility

(2) The potential for chaos

All workplaces (from start-up businesses to international corporations) involve a large number of ‘moving parts’. These parts are highly interdependent. Knock one out of kilter and the whole edifice can be disrupted.

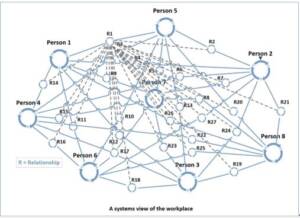

This networked characteristic of social organisations of this kind can be represented graphically as follows:

As shown above, each individual in a social network is also a system in themselves: a system comprising agency, emotion, intellect, physicality and aspiration (alongside many other characteristics).

Between any two individuals in any network a further subsystem arises: the relationship between those individuals. These relationships are depicted here as R1, R2, R3 etc.

And between each of these ‘relationship entities’ a further subsystem applies: the relationship between each relationship. These subsystems are worth emphasising because the way I interact with you is witnessed by others. It will affect how they interact with their colleagues. (To avoid confusion I show these for only the first relationship, R1, above.)

But please don’t let this complexity alarm you. The message to take away from this is straightforward. It is that every member of an organisation is connected, directly or indirectly, to every other member. The impacts of our actions cascade outwards through the complex adaptive system of our business. Therefore everything you do has the potential to impact the whole system and everyone within it… Therefore no one is irrelevant. Everyone matters.

The inherent precariousness and fragility of complex systems such as workplaces and businesses is addressed through a range of control mechanisms. Hence the term ‘adaptive’. Without these checks and balances our organisations would not survive. HR policies, mission statements, rules, regulations, contracts of employment and formal business processes are all examples of such controls. You could say that every business is a balancing act. Get the balance wrong in one direction and you stifle creativity and the ability to adapt; get it wrong in the opposite direction and your company or business becomes chaotic and in all probability fails.

A systems view of the workplace – We are all interconnected. No one is irrelevant. Everyone matters |

The second perspective I’d like to introduce to this discussion is that of Complexity Theory and non-linear dynamics. Again, please don’t let this terminology put you off… Just as with systems theory, there is a simple message to be taken from complexity theory, which I’ll come to shortly.

Firstly, we should note that there are many straightforward causal processes in our everyday working lives. You press the touch pad on a photocopier and your copy is produced. You click on an icon and an app kicks into life. You press a button and an engine or device is activated: an automated process comes into play.

These are examples of (or metaphors for) linear dynamics: the simple, direct, causal processes you would expect of Newtonian physics, of one object ricocheting off another, of any action creating an equal and predictable reaction.

Non-linear systems are very different. In non-linear systems there is no simple relationship between cause and effect. In these systems the causal linkage is more complex and less predictable. Examples of non-linear systems might be the economy, or the weather, or, as we have seen above, the workplace.

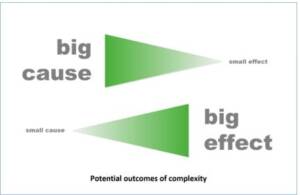

Complexity theory tells us that in complex systems small changes can have disproportionately large affects. A famously cited example is the butterfly flapping its wings in New Mexico and causing a hurricane in China – the so-called ‘butterfly effect’.

In terms of our day-to-day lives this is by no means a natural intuition. Intuitively we expect large-scale effects to need large scale causes. For example, if we wish to make a significant change to the productivity of our company we assume a need for considerable investment in new technology or training. If we need to tackle a problem with company morale, we think of extensive PR campaigns, comprehensive changes to benefits, or staff reorganisations.

But the science of complexity indicates that this may not be the right approach. You may make large changes and have little impact… and you may make small changes to dramatic effect.

This perspective of the complex, dynamic and non-linear workplace environment allows me to come to a further important and – dare I say it? – thrilling conclusion.

It is the conclusion that we are more powerful than we think. It means that from the CEO to the cleaner, from the HR Director to those working on the front desk or the production line, we are all important. Our smallest actions can have dramatic consequences. We sometimes feel as if we are mere cogs in a larger machine, but we are cogs whose actions can have consequences which far outweigh their initial appearance of insignificance.

This is what contemporary science and mathematics tells us – and, as is often the case with new scientific theories, it is something which will soon come to be seen as common sense.

A lesson from complexity theory – Dramatic consequences can result from our smallest actions |

So now we come to ethics.

We have seen that:

These considerations position us to answer a powerful challenge: “Why should I be moral? Why me? And why now?”

The answer is a simple elaboration of the bullet points above.

You should be moral because everything you bring to the workplace – including your morality – combines with what others bring to the workplace to create the organisation within which you work.

You should be moral because your actions or behaviours can affect the contacts of your contacts and the colleagues of your colleagues – and their colleagues too.

You should be moral because even the smallest of your actions can have far reaching consequences – and far greater impacts than you might intuitively expect.

This is the nature of complex systems, and it is the nature of morality, too.

A lesson from systems theory – You are more powerful than you think – and with power, even potential power, comes the duty to use your power ethically

|

My next article continues our discussion of the ethical colleague by asking what it is we bring to the businesses within which we work. Are we merely ‘Work Delivery Units’ or are we something more?

Read more articles on our Phase 3 Insights page

About the Author:

Luke Andreski is a writer with over thirty years’ experience in the IT industry, specialising in People Technology implementation projects and change management. More recently he has focused on moral philosophy and psychology, with a particular interest in business leadership and management ethics.

He is currently working in conjunction with Phase 3 on a series of articles investigating Ethics in the Workplace.